It’s easy to imagine that stories are for bedtime reading, not business writing. But there’s good reason to challenge that assumption.

Using some of the classic elements and structures of storytelling will appeal to an intrinsic and emotional part of your audience’s minds, and make many things you write or present at work more effective and more engaging. This is what we’ll be exploring in this article.

And if you’re sitting comfortably, we can begin.

The importance of storytelling

Storytelling is everywhere. Of course, it’s in the books you read, the songs you listen to and the films you watch. There’s a reason Netflix and Disney are so successful (hint: it’s because they’re in the business of selling stories). But storytelling is also peppered throughout your day in places you might not expect.

Storytelling is on the news – even though news stories are (we assume) non-fiction, they’re still stories. And the way they’re communicated to us follows a structure designed to deliver a narrative in a way that we’ll find most clear and engaging.

It’s on Twitter – where we write and read bitesize stories so addictive that we spend hours a day scrolling through them.

It’s in memes and emojis on Facebook and in our group chats – visual aids we use to hyperbolically explain our moods, thoughts and feelings.

Andy Murray’s tweet telling the story of his wedding through emojis

Open description of image

Tweet from Andy Murray, at 9.40am on 11 April 2015, consisting entirely of the following emoji:

Sun with face, umbrella with rain drops, face with tears of joy, necktie, nail polish, person getting haircut, face with tears of joy, woman with veil, face with tears of joy, automobile, wedding, woman dancing, woman and man holding hands, folded hands, ring, kiss, clapping hands, memo, musical keyboard, camera, movie camera, automobile, wine glass, fork and knife, birthday cake, confetti ball, party popper, people with bunny ears, musical notes, microphone, tropical drink, clinking beer mugs, wine glass, beer mug, doughnut, soft ice cream, wine glass, tropical drink, cocktail glass, beer mug, crescent moon, red heart, two hearts, face blowing a kiss, ZZZ, ZZZ, ZZZ, ZZZ, ZZZ, ZZZ, ZZZ

The tweet has 26.1K likes and 1.8K comments.

An innate art …

You’re storytelling all the time without realising it. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has called our brains ‘story processors’ because storytelling is so intrinsic to how we operate, it’s akin to breathing. We’re not as logical as we like to think, and instead leap to assumptions about our reality based on limited information. In other words, we fill in the gaps in our knowledge by telling ourselves stories.

When someone asks ‘How are you?’, within milliseconds your brain is recalling information, working out what’s relevant, deciding what you want to share, the tone in which you want to share it. It’s structuring the information then formulating the story of your recent life into words.

… and a science

Storytelling is interesting because it’s an art but also a science.

Of course, storytelling is a creative endeavour, because it’s the art of taking basic information and applying imagination. The Lord of the Rings wouldn’t have been as successful if the novel had only read ‘Small man journeys to destroy a ring’. It’s the art that J R R Tolkien applied to that basic information that created one of the most successful novels and film franchises of the 20th and 21st centuries.

But by looking at the scientific part of storytelling, we can uncover how to learn the skill and apply it to any kind of writing we do. And the science has a lot to do with structure.

[Sidenote: If you’re interested in the science and psychology behind storytelling, I can’t recommend Will Storr’s The Science of Storytelling enough. It is the most captivating book, rich with examples from popular culture, and a fascinating look at why storytelling makes us human, in all our flaws and all our joy.]

All good storytelling follows roughly the same structure: there’s a main character, there are three acts, there’s a heroic journey, there’s a climax, there’s a resolution.

These elements are in every story you know. It’s often called a storytelling arc, or the hero’s journey. And the formula takes the audience from one place to another, then back to the starting place that is in some way better now. It’s amazing how even the shortest story can have this structure.

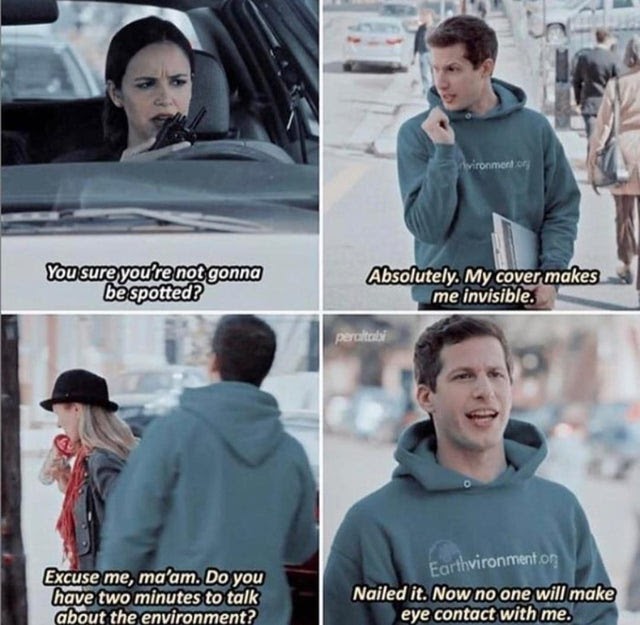

Take this meme, for example:

Open description and transcript of image

Four-image meme with captioned screenshots from the TV show Brooklyn Nine-Nine.

Image one: A Latina woman sits behind the wheel of a car speaking into a walkie-talkie. The caption reads: ‘You sure you’re not gonna be spotted?’

Image two: A Caucasian man stands on a street. He is holding a clipboard and wearing a hoodie reading ‘Earthvironment.org’ and speaks into a wire concealed under his shirt. The caption reads: ‘Absolutely. My cover makes me invisible.’

Image three: The man is seen from behind addressing a woman passing by who is ignoring him. The caption reads: ‘Excuse me, ma’am. Do you have two minutes to talk about the environment?’

Image four: The man, alone again, looks triumphant. The caption reads: ‘Nailed it. Now no one will make eye contact with me.’

There’s a main character (the man in the hoodie). There are three acts (beginning, middle, end). And there’s a heroic journey (the man wants to be invisible for whatever reason and succeeds), with a climax (he tries out his theory – will it work …?) and a resolution (he has avoided eye contact and is pleased).

Once you know these rules of how to structure a story, it’s a simple formula you can apply to any writing where you need to engage, persuade or get people to part with cash.

How we use stories

As humans, we use stories to understand and find meaning in things. Stories are how we make sense of a world that is largely out of our control. We use them to decide who we are and what we think. We need stories to assert our identity (who we are, what we believe in and why) and decide our morality and values (what is right, what is wrong, who are our allies and who are our villains).

For example, you might decide you’re a dog person, not a cat person. And you’ll probably come to that decision based on the experiences you’ve had with those animals. You’ll tell yourself how you relate more to dogs than cats because in some way they mirror back the same personality traits as you.

You’ll decide a dog’s morality aligns more with your way of seeing the world than a cat’s. Which, of course, isn’t rational. But this will be the reason you decide to get a dog (or cat), feed it, care for its welfare and hang out with it for years of your life. That’s the power of storytelling.

A shared world view with our pets? It might be a stretch

Image credit: Drazen Zigic / Shutterstock

In a business context, we constantly need to make decisions or get others to understand our way of thinking, to gain alliances and secure budgets. This is why having a good understanding of storytelling is vital. It can be a powerful tool for persuasion.

Our need for meaning

When we’re trying to work out what we think about something or discovering something new, we need the information to be presented in a way that we can attach meaning to. This is how we decide whether we align ourselves with it or not.

If the structure isn’t there, we’ll create a story by ourselves to make sense of the new information. We’ll think ‘This must have happened because of that.’ Which may or may not be correct. The point is, we’ll imagine the truth based on our own previous experience and the information we have available.

All purchasing decisions are emotional decisions. Even professional ones. We need to be able to attach meaning to information in order to have an emotional reaction.

This is why it’s always a great idea to already have the story you want to tell in mind when writing in a business context. If you haven’t created a narrative for your decision-makers to follow, they’ll create their own – which might not have the positive emotional outcome you want.

Open description and transcript of image

Quote from AZ Quotes attributed to author Jonathan Gottschall, with headshot.

Quote reads: The storytelling mind is allergic to uncertainty, randomness, and coincidence. It is addicted to meaning. If the storytelling mind cannot find meaningful patterns in the world, it will try to impose them. In short, the storytelling mind is a factory that churns out true stories when it can, but will manufacture lies when it can’t.

Often, when we write at work, we are looking to persuade people. Whether you’re submitting a bid, writing a case study, creating a strategic presentation or writing internal or external communications – your aim is to convince colleagues of your point of view or decision-makers to buy, sell, sign off or agree to a project.

Using a storytelling structure in any of these contexts will appeal to the humanity of whomever you’re writing for or presenting to. If you appeal to their human nature, you’ll hold their attention, keep them engaged and increase the likelihood of them agreeing with you.

A business legacy

The great thing about stories is they live on after you’ve put them into the world. Once you’ve found or developed a good story for a case study or a proposal, you can recycle it in many different ways and increase its power. This also means stories are well worth your time in finding and developing.

For example, you may write a great case study about how a hero (your client) had a problem. They embarked on a journey to overcome the problem (the hero’s journey), found your services (a story arc) and are now in a better position than they started in (a happy ending).

In a case study, your client is usually the hero

Open description and transcript of image

Screenshot of case study on the Emphasis website, with YMCA logo.

Visible text reads:

How a tiny team at a children’s charity won the biggest contract of their lives

When the local authority announced it was changing the structure of the family support service in Hertfordshire, charity One YMCA faced writing the biggest bid in its history – or losing £500,000 in funding.

Once you have that story, you can use it:

- during sales calls with prospective clients and while networking

- in reports to show success to your board

- to increase employee awareness and engagement via internal messaging (for example, in internal newsletters and emails, on the intranet, on Slack)

- in any presentation that shows the value of what you do.

Why you should be using storytelling in business

Storytelling belongs in pretty much any writing you do to serve the business. Without realising it, you’re probably already telling stories constantly – to improve the understanding of what it is you do and the value you bring as a business. Business storytelling is vital for communicating your value and for giving your employees reasons to believe in the work you’re doing.

Three benefits of using storytelling in business

You can use a storytelling technique in many business-related writing contexts to improve readability and understanding, ensure your communications are audience-focused and keep your employees engaged.

1. Improving readability and understanding

Using a storytelling structure improves the readability of your document (or flow of your presentation) because it helps you formalise your thinking into a tighter, more engaging structure than using a more typical strategic narrative.

I always like to point out that business people are people too – because there’s no reason corporate writing or B2B marketing should be boring. We’re all human beings who want to feel like we’re making good decisions. And stories help us to communicate what we’re saying effectively, in a way that appeals to our audience’s human nature.

2. Ensuring your communications are audience-focused

Storytelling keeps your focus firmly on the audience. The point of storytelling is to evoke emotion in order to align the audience with your way of thinking: you have to start out with your intended readers in mind, understanding them and knowing the emotion you’re trying to evoke.

And when you can do this well, it helps you to better communicate your value.

3. Keeping your employees engaged

Internal storytelling is vital for morale and helps employees see the bigger picture. Inspiring your employees with the real-life stories of how their teamwork creates results for your clients is a big part of attracting and retaining the best talent. We all need to feel the positive impact of our work or we’ll become disinterested and disengaged.

How to identify stories worth telling

Often, the teams who are privy to the really good stories in your business won’t be the ones writing them. For example, the people ‘in the field’ – either doing the client work or working directly with service users – are too busy doing just that to be identifying good storytelling opportunities too. Meanwhile, it’s often the marketing or content teams – who generally don’t have that direct contact – who are expected to find and write the juicy stories of success to inspire internally or externally.

So how do you make sure you’ve got a constant stream of storytelling ideas coming through to the right people? Here are a few ideas:

1. Schedule a monthly meeting with the people who you think are privy to the good news stories about your business. Interview them to uncover conversations they’ve had, projects they’ve been involved in and anything else they have found interesting lately from being entrenched in the work.

2. Use internal channels to reach out to people and teams you don’t usually work with for catch-ups. Nothing beats talking to people to gather information and get access to stories you’ll miss otherwise.

3. If appropriate, reach out to clients or service users to get their real-life stories of how your business has benefitted them.

4. If your business has social media, read through the comments to find anyone who seems like they might have a positive story to tell about using your products or services. Could you create a case study with them?

Questions to ask yourself that might help you to identify stories worth telling about your business:

- Who has used your products or services recently? What success have they had as a result?

- What’s the story of that project you have just completed? How did you make it successful? How did it start, what did you do and how did it finish?

- What’s going on culturally in your business? Are you striving to be more sustainable, for example? How’s your journey going?

- What’s going on in your sector in general? What do you think about your current position, and how are your employees feeling about it?

How to tell an effective story

An effective story is one that grabs attention at the start and holds it to the end, with each section leading to the next.

The best way to plan an effective story is to know the destination you want to take your audience to – the emotion you want them to feel or the action you want them to take. Knowing this before you start writing is key because it helps you structure the key information that will lead up to that point and ensure your writing is reader-focused.

If you’re writing to gain alliance or to secure a budget for a project, setting out your argument in a storytelling structure will allow your decision-makers to see and feel the story of a project – the start, middle, end and the benefits of following your narrative.

An effective storytelling structure takes the audience from start to middle to end. These sections generally move through a narrative where the hero of the story has a problem they need to overcome and they gain some kind of enlightenment along the way. Again, this is known as the ‘hero’s journey’, and it’s a formula used in most great novels, films and TV shows.

The hero’s journey

Image credit: anonymous poster / Wikimedia

Open description and transcript of image

Circular diagram labelled ‘The Hero’s Journey’. Annotations run clockwise around the circle to describe the progression, with the circle (and journey) divided horizontally into ‘Known’ and ‘Unknown’. The annotations read:

Known:

- Call to adventure

- Supernatural aid

- Threshold guardian(s)

Unknown:

- Threshold (beginning of transformation)

- Helper

- Mentor

- Challenges and temptations

- Helper

- Revelation

- Abyss: death and rebirth

- Transformation

- Atonement

Known:

- (Gift of the Goddess)

- Return

Structuring an engaging story

This is the structure of most effective storytelling:

Start

We start in normality. Effective narratives always start rooted in normal life, whatever ‘normal’ is for the hero of the story. As the audience, we need to know what the normal context is in order to know what the change is when it happens.

Something then happens to upset that normality. A change occurs that presents a challenge, and the hero needs to react or seek something in order to overcome the challenge and get back to normality.

Middle

The hero goes on a journey of discovery (either physically or mentally) to overcome the challenge or react to the change.

There is some sort of climax where the elements of the story come together in chaotic glory and the hero has to find a way through the chaos to reach a positive outcome.

End

The climactic section of the story ends. And the hero has not only overcome the challenge but has come out enriched because of the experience of the challenge.

How a storytelling structure works in practice

To see how this structure works in practice, let’s take a classic story from one of Disney’s most popular animations: The Lion King.

Start

The Lion King starts in ‘normality’, which in this case is Pride Rock in Africa, where King Mufasa and his queen rule the animal kingdom. They present their lion cub Simba to their animal subjects, who bow down in respect.

Early on, we meet the threat that might upset that normality – Scar, Mufasa’s brother, who wants to steal the throne from Simba. So, the scene is set, and we have a possible change on the horizon.

Middle

The threat becomes real when Scar kills Mufasa and drives Simba out of Pride Rock, blaming Mufasa’s death on him so he can never return to his rightful home.

This triggers a hero’s journey for Simba as he flees in shame. He’s alone and nearly dies but is rescued by outcasts Timon and Pumbaa, who become his friends. He lives his life away from his home of Pride Rock, convinced his community is better off without him.

After some time, Simba has a chance encounter with an old friend from his childhood, Nala. She informs him that Scar has let Pride Rock descend into famine and Simba’s kingdom needs him to return and reclaim his throne. This marks the climax of the story as they return together to battle with Scar.

End

Back at Pride Rock, Simba defeats evil Scar. And, having learned his father’s death was not his fault, claims his rightful place as leader of the animal kingdom. Harmony, peace and normality are restored.

Simba comes full circle as the hero of the story. He doubted his rightful place as Lion King, but he defeated the threat, and we end the story in a scene that recalls the beginning – with Simba presenting his and Nala’s lion cub to the kingdom.

‘Real’ stories

Storytelling isn’t just limited to fiction. Non-fiction TV shows like The X Factor and The Apprentice also follow a storytelling structure. TV producers will orchestrate plot lines out of real-life characters to assume a structure like this because they know how addictive it is for a viewer.

When we meet a contestant on shows like The X Factor, for example, we always hear their backstory. We learn where they’re from, the hardships they’ve overcome to get here and why this is so important to them.

Producers include this so we feel invested in the contestant’s apparent hero’s journey and are rooting for them when they face the judges. We care deeply about their success because we expect to see that same well-used narrative arc – from underdog to hero.

Yes, you should be telling tales at work … Business storytelling is vital for communicating your value and for giving your employees reasons to believe in the work you’re doing @EmphasisWriting Share on X

Why this structure works

As soon as we’re introduced to the hero, we’re led to care about what happens to them. We empathise with them immediately when we’re given enough information about them: their hopes and dreams and what makes them flawed.

We’re also hardwired to respond to change because it challenges our sense of stability. So when we start a narrative with a hero and then introduce change, it triggers us to care what happens next.

The hero of a story can be anyone – an individual, a group of people, your client. When crafting a story in order to persuade someone, the key is to make it clear who the hero is, in order for the audience to empathise with them – to see themselves in the hero’s shoes. And for them to follow themselves through the story and see how they will become enriched, enlightened or in some way better off if they cooperate with the steps you’ve laid out in the narrative.

When and how to use storytelling in business

So, hopefully you’re already convinced that storytelling isn’t only for Disney and reality TV. It absolutely belongs in business too – and incorporating it into your documents and communications at work will make them much more effective.

Let’s look at some common contexts where storytelling can help you improve your communication and how to do it.

Business cases, proposals and bids

Whether you’re writing a business case, a proposal or a bid, your purpose is to persuade. You can help decision-makers to understand your case by using a storytelling technique to establish the need for your services, the project or investment.

This is how a storytelling structure could look when you’re writing a business case, proposal or bid:

Set the scene: Describe the business context. Outline where the client or project is right now in the context of ‘normality’. This could mean within their business specifically. Or it might mean explaining where the sector is in a general sense. For example, is it doing well? Is it failing? Then explain how the business fits into that context.

Describe the threat: Be bold when introducing the threat. What has happened to upset the usual way of things? Is there growing competition? Diminishing demand? A lack of focus or funding?

Identify the challenge: Lay out the business case and show what the cost is of not acting: ‘If we don’t do X then Y will be the result.’ If you have a specific case study example of a real-life consequence of inaction, include it here.

For example, if you need new updated equipment, what has been a consequence of not having it? Has it directly impacted you in not being able to fulfil your job properly? Who has that negatively affected and how? Or, if you’re writing a proposal or bidding for work, what will be the direct consequence of the client not acting? Will they lose money, value, their audience? Use specific examples.

Where you want to be: Paint a picture of how things will be when you get what you’re asking for. Rather than listing benefits, let your decision-makers see how much better it will be. Let them envision the better version of the world you’re suggesting. Use phrases like ‘When we get this …’ rather than ‘If you agree to this …’. This is all about showing them the happy ending your solution provides.

Pro tip: If possible, always try to turn any kind of business storytelling into a presentation you give either over video call or in person, rather than sending it over in a document. People buy from people they like. And they’re more likely to like you and your story if they can see and hear you.

Take the opportunity to present your stories in person (or face to face online) when you can

Image credit: garetsworkshop / Shutterstock

Case studies

Case studies are a great opportunity to fine-tune your storytelling skills. They also give you the chance to play a pivotal role in the story.

When you’re entrenched in the work, it can be hard to step away and see the bigger picture of your work and the impact it has had. Case studies formalise the work into a neat start, middle and end format, forcing you to distil the complexities of a project into a short, snappy heroic tale.

In case studies, you’ll often want your client to play the part of the hero. Since case studies are chiefly marketing content, you want future prospects to read them and see themselves able to step into the heroic footsteps of your past clients.

In these cases, your company plays the part of the mentor or helper (another feature in the hero’s journey) who sets the hero on their way. Yes, the client saves the day – but they couldn’t have done it without you!

There are some times when you may want to step into the hero’s role. For example, in internal communications where you want to increase engagement and raise awareness about the difference your company is making, or when you need to make the significance of your work clear when you’re in a jargon-heavy or technical industry.

This is how a storytelling structure could look when you’re writing a case study:

What was the challenge? Lay out the challenge that you or your client needed to overcome. Use a formula like this: A was here. But if A didn’t do B, then X, Y and Z.

What did you do? A case study is all about showing value. So be specific about the story of what you did to overcome the challenge – or what the client did (with your help, of course). Include any issues you or the client faced along the way and how you or they overcame them too.

Why was it great? What were the results? What did your solution achieve? Make it really clear what was different by the end.

If you are gathering case studies from individual clients or customers, interview them and use this before-during-after formula to dig into the story of their ultimate success – and the journey they took to get there. You’ll get some great quotes!

Once you’ve written your case study stories, you can tweak them to use in many different ways. They can be used in website content and social media posts – as well as in internal newsletters to boost employee engagement and morale.

Case studies are also indispensable sales tools – giving your sales team anecdotes they can use in sales calls and meetings, as well as documentation they can include in bids as evidence of previous successes.

Internal and external communications

Employee engagement is hard. Community engagement of any kind can be hard. It can be difficult to get people to listen or care when you’re a large organisation – or if you need employees to engage with what is (at least on the surface) quite dry or technical information. Taking a storytelling approach will help.

Whether you’re writing for an internal or an external audience, they want key information:

- quickly

- in an engaging way

- in a format that’s easy to understand.

Here are a few tips for making internal and external communications better with a storytelling approach:

What is the story?

This seems like an obvious point, but simply asking yourself this before you start writing is fundamental to creating something engaging. Rather than just giving people the key (possibly dry) information you have to share, consider why you’re giving this update.

For example, if you’re letting an internal audience know about a change in policy, don’t simply tell them there’s been a change in policy. Be transparent and explain the reasons why there has been a change and what it means for them in their lives. If you have specific examples (ideally relatable, people-focused ones), use them.

Why should the audience care?

How will this update affect your audience? What benefit is in it for them? What will happen as a result?

What’s the onward journey?

And finally, don’t forget to let the audience know what you’d like them to do with this story. Is there further reading or an action you want them to take?

Pro tips:

1. Keep it brief: Summarise the beginning, middle and end of the story briefly. Internal and external audiences are usually strapped for time, so think about how to communicate your messaging in a short, snappy way, rather than a long, meandering narrative. Using short sentences and short paragraphs will help. So does going through your writing and deleting unnecessary words.

2. Keep it clear: Your tone of voice matters. Avoid overly formal language as much as possible. Writing as you would speak (within reason) often better guides the eye through the words and helps a reader understand what you’re saying more quickly.

You can do this by:

- using simple English (use everyday words rather than complex words)

- using the active voice (eg ‘Sarah plays the guitar’ rather than the passive ‘The guitar is played by Sarah’)

- being specific rather than general (specific examples help people empathise).

3. Use visuals: To help people understand what you’re saying, use key visuals relevant to the story you’re telling. For example, if you’re updating an internal audience on a new hire, use a photo of the person. If you’re updating an external audience on a new product or service, use a beautiful image of that product or service in action.

In conclusion (aka the happy ending)

We all love stories. Great writing uses storytelling elements because it appeals to our innate need for stories – as a mechanism for taking in information and understanding the world.

We’re already storytellers in our day-to-day lives, whether we realise it or not. And actively bringing a little storytelling magic into our business writing can hugely improve the engagement levels of our communications, both inside and out of our organisations.

If you’re struggling to engage an internal or external audience and need to bring storytelling into your communications, get in touch with us and we can design a storytelling workshop specifically for your business.

Main image credit: Mr.Whiskey / Shutterstock